A few years ago, I wrote this brief post, after Scott Hanselman re-tweeted one of his blog posts from 2012. In the wake of last year’s takeover of Twitter by Elon Musk, I’ve been pointing people to Hanselman’s decade+ old advice because I’m seeing it repeated in various forms by others (Monique Judge of The Verge is the most recent example I’ve read). In the time since that November 2019 post, I’ve published at least 60 posts (with a couple dozen more still in drafts). But the best-written and fiercest piece I’ve read on the subject is this Substack post by Catherynne M. Valente.

Her piece is well worth reading in full and sharing with friends. I’m just 5 years older than Valente, and reading it gave me a flashback to the very first page I ever put on the web. It was probably back in 1994, since the Mosaic browser had just come out the year before. I was a sophomore computer science major at University of Maryland then, so it would have been wherever they let students host their own pages. It was just some fan page for the team they used to call the Washington Redskins. I somehow figured out how to take an image of the team’s helmet and make it look debossed under everything else I put on the page. It was the first time I got compliments from strangers for something I did on the internet (in a Usenet newsgroup for fans of the team). Usenet is how I joined my first fantasy football league. Many of the guys I met online in that league back in 1993 are still friends of mine today. I later met a number of them in-person when I visited the Pacific Northwest for the first time (and I’ve been back a couple more times since). Usenet is how dozens of us Redskins fans ultimately met in-person and attended a Redskins game together in San Diego (LaDainian Tomlinson’s rookie debut in 2001, and Jeff George’s debut as Redskins starting QB). So much life has happened since then that until I read a post like Valente’s, it’s very easy to forget all the different ways in which much less sophisticated tech than we have today proved to be very, very good at helping us make meaningful, durable connections with each other.

The 12-point plan of how online communities are created and ultimately destroyed is the heart of her piece. A lot of the friends I first made on on Usenet, or even email distros have migrated through a lot of the same sites Valente listed as having fallen victim to that plan. The migrations to Mastodon (or Instagram, or Slack, or Discord, or Reddit, or SMS groupchats, etc) sparked by Twitter turning into $8chan (as some only half-joking call it now) is a reminder of many previous site & app migrations. Personally, I’m splitting the difference–spending a bit more time on Slack with friends, an ongoing chat with my cousins via GroupMe, and more time on Mastodon in favor of a bit less time on Twitter (less doomscrolling at least). Particularly in the depths of the pandemic (which sadly still seems far from over), some of my Twitter mutuals found and formed a real community in a direct message group. There are nearly 20 of us, all black, in business, tech, academia, science, and journalism among other fields. They’ve been some of the most encouraging people regarding my writing beyond my own family. One of them gave me the opportunity to be a panelist on a discussion of diversity in tech. I continue to learn from them through our ongoing conversations and value our connections enough to have shared other contact info with them if Twitter does go down.

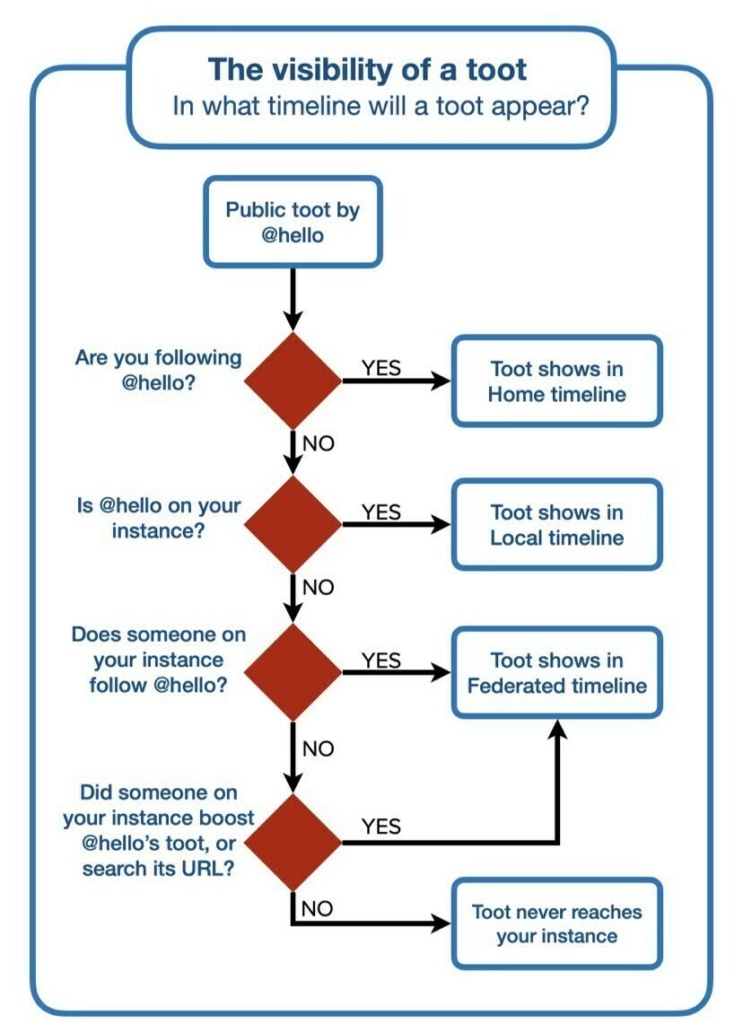

Some of us have already learned that the grass isn’t always greener elsewhere when it comes to social media. What’s being done to Twitter by Elon Musk right now–as much value as I still personally gain from using it–has been an opportunity to reconsider how I engage with social media. I’ve been much more selective about who I follow on Mastodon (just 85 people vs over 800 on Twitter) and am seeing a lot more technical content as a result. This change in my social media experience is intriguing enough that by this time next year I may be one of those people who went from having just a basic grasp of how Mastodon worked to self-hosting an instance and writing all about the experience.